Time’s Twisted Arrow: An Examination of Queer Desynchronization

Evelyn Meckley

Introduction

Watching my roommate and me in our dorm on any given Friday night, it would not be difficult to tell which of us was the queer one. My roommate whirls around the room, clipping on jewelry, painting on make-up—a social butterfly in full flutter, readying herself for a night of revelry ahead. I’m already in my pajamas, headphones on, laptop open, watching her. There’s no meanness in my gaze, nor even jealousy—just honest, baffled curiosity.

She, with her multiple past boyfriends and weekly cruise of the party scene, baffles me. In those moments, on those evenings, she could represent all of society: familiar and yet utterly foreign to me, the quiet, queer outsider sitting cross-legged in her pajamas. I’m familiar with these motions she goes through because they are what every eighteen-year-old is supposed to go through, according to society’s cisheteronormative standards. Equally are they foreign to me, because I have absolutely no lived experience with them. My timeline diverged abruptly from my roommate’s, from society’s at large, when I realized that I was queer in ninth grade.

Queer time is—crucially, appropriately, and somewhat humorously—not straight. That is to say, queer time does not follow a linear path. A typical cisgender and heterosexual timeline is simple: first crush, first kiss, first date, first (opposite-sex) partner… and after the firsts come marriage, children, a house together. These are the chrononormative benchmarks you are expected to meet. Nowhere in that straightforward chronology is there time for debating if you are a different gender than you were assigned at birth or whether you experience any sexual or romantic attraction whatsoever. These types of internal struggles contribute to what Thomas Fuchs (2001) refers to as “an uncoupling in the temporal relation of… individual and society”: a desynchronization from normative time (p. 180). Fuchs, a phenomenological psychologist, uses the concept of desynchronization to explain clinical depression; in this paper, I will use it to recontextualize queer temporal experience, as there are notable disconnects between cisheteronormative time and queer time that can be better understood through the lens of a temporal “uncoupling.”

In this autoethnography, I will explore how queer people experience desynchronization from chrononormative benchmarks. Through analysis of queer media, research into queer time, and interviews with queer people, I will examine how queerness leads to the formation of unique and distinctly non-linear timelines—beginning with the initial divergence from chrononormativity, continuing through the often twisted and circuitous temporal experiences that characterize queer self-exploration and ending with a look toward non-normative futures. Desynchronization can be a profoundly isolating experience. By centering non-normative narratives, I hope to bridge the temporal divides created by queer divergence from chrononormativity and foster a deeper understanding of the unique ways queer people interact with society and its cisheteronormative standards. As many in the queer community are not straight, neither are our experiences of time’s arrow.

The Initial Branching

I just know that I might not be straight anymore… and now I’m terrified.

(E. Meckley, personal communication, February 8, 2018)

Recognition of oneself as queer, often colloquially referred to as one’s “gay awakening,” marks the first divergence from normative, linear time. This can be a period of great relief or a period of deep loss—or a complicated mixture of the two. A gay awakening is, fundamentally, a rip from linear time, which can be profoundly disturbing. I certainly found it so; I was, indeed, “terrified” to find myself suddenly untethered from the timeline I had assumed I would adhere to. It was not only myself who had made such an assumption: any time I insinuated that I might not want to have children, my mother would gloss over the hint. Any discussions of my future spouse always used the word “husband,” contradicting my nascent understanding of my bisexuality. My gay awakening marked a divide between how I understood myself and how everyone else understood me; this, I perceived as a loss, a separation from common time where “spouse” meaning “husband” was a fact taken for granted. However, for all my fear, I also found a measure of comfort in the new possibility for a queerer future.

Similarly, for some queer individuals, discovering the existence of the queer community is a moment of revitalizing clarity and self-discovery. Here, what gender scholar Kathryn Bond Stockton (2009) refers to as the “protogay” child finally learns the words to identify themself. This recognition, framed as a welcome revelation, often coincides with a “reject[ion of] the heteronormative fantasy of adulthood,” leading the individuals involved to “develop a relationship to time itself that is decidedly queer” (Jaffe, 2018, para. 6). This bold rejection of chrononormative benchmarks stems from an initial defiant divergence from cisheteronormative time, the first branch in a deliberately non-linear path that is purposefully, joyfully queer. A gay awakening, the birth of the newly queer individual, can be the starting point of an eagerly anticipated journey.

However, a gay awakening is also a death: the death of the cishet (cisgender and heterosexual/heteroromantic) version of oneself. Interviewed about her mother’s reaction to her lesbianism, my friend “Allyna” replied that “[My mom] still wants me to be bi, so I still have the option of being with a man and having kids. She’s cried to me about that before” (personal communication, November 6, 2021). Although Allyna “would love to get married someday… [and] would love to have kids,” her mother still mourns the straight future that died with her coming out. That sense of loss can also be felt by the queer individuals themselves, as internalized queerphobia and fear for their newly uncertain future causes them to mourn the surety that comes with adherence to cisheteronormative standards. There is an implicit promise of a future following cisheteronormative time—you will get married, you will have children, you will be secure and loved—and upon realizing one’s queerness, that promise dissolves.

Sometimes, queer people subconsciously resist this dissolution. Both I and the two queer women I interviewed identified as bisexual when we first realized our queerness. As Allyna put it, “…if you’re not straight, and you don’t know that you’re fully gay, you go bi” (personal communication, November 6, 2021). My friend “Sawyer,” also a lesbian, noted that the transition from straight to bisexual to lesbian was a common pattern she’d noticed amongst other gay women (personal communication, November 5, 2021). Now, rather than bisexual, I suspect myself to be on the asexual and aromantic spectrums; given that I once feared what I perceived as aromanticism’s threat to my cisheteronormative future, “going bi” was the safer option.

Of course, bisexuality is not “straighter” than homosexuality, and not all bisexuals are on the road to other sexualities. But for many, bisexuality presents a sensible middle ground between the extremes of monosexuality: a waystation identity where queerness can be explored but the cisheteronormative future is still assured. This is a false assurance, however. Bisexual or not, the queer awakening calls the cisheteronormative future into question unavoidably and irrevocably. It wasn’t until my bisexual awakening that I began to doubt my ability to adhere to a chrononormative timeline; with that first seed of doubt planted, despite the possibility for me to have a husband and children, my safe, heteronormative future fell apart before my eyes.

The loss of the cisheteronormative future is part of a critical desynchronization in a queer person’s temporal experience, as the individual’s sense of their past and future is reanalyzed with their new self-understanding. Sometimes, an identity crisis results. Fuchs (2001) describes such crises arising

as serious reactions to a desynchronization: Former orientations… have become anachronistic. The necessary development, however, is dammed back. A new homoeostasis is not to be attained without a break or ‘time-out’, a phase of disorientation and dying of the past. (p. 182)

The “damming back” can be attributed to the mourning period of queer realization: as the supposedly straight past and now-unreachable straight future die, it takes the individual time to overcome the subsequent loss, which further widens the gap between the temporal positions of the individual and cisheteronormative society. Desynchronization has led to crisis; the crisis has only worsened the desynchronization. While, eventually, the queer individual resolves their identity crisis (often through “painful processes such as grief, renunciation, re-evaluation and re-interpretation”), their timeline is permanently marked by this early divergence and retardation (Fuchs, 2001, p. 182). No longer does time’s arrow point forward; instead, it curves away, diverted and delayed, never to take the straight path again.

Twisted Temporalities

This is gonna be a few rough years or so, isn't it? Because that's how long it'll take me to beat this thing around. I never make anything easy on myself.

(E. Meckley, personal communication, February 8, 2018)

In the disturbingly prescient journal entry above, I accurately predicted the course of my queer journey from freshman year of high school to freshman year of college: a relentless cycle of sexuality crises, short-term conclusions that inevitably bowed beneath the weight of my doubt. The desynchronization and identity crises that often follow a gay awakening are, unfortunately, not one-off events. Rather, they can come to define a queer timeline, reappearing and recurring, continuing to distort any remaining semblance of linearity in myriad ways. Like the twist of a plot taking characters somewhere they didn’t foresee or the twist in your stomach when you realize a new truth about yourself, so does the queer path twist: unexpectedly and often uncomfortably.

These twists can be internally motivated, with no discernible trigger. My frequent desynchronizations with linear time due to questioning my sexuality were not caused externally—instead, I simply found myself consumed with a need to pin down my shifting identity. A recent journal entry of mine bemoans:

Straight doesn't feel right, I don't think, but I dunno if bi feels right either, and I don't think lesbian is right… nothing's going to fix the fact that I don't feel right. Ace [asexual] doesn't feel right. Aro[mantic] doesn't feel right. What is right? Do people feel that? How do you know, for sure? (E. Meckley, personal communication, August 8, 2021)

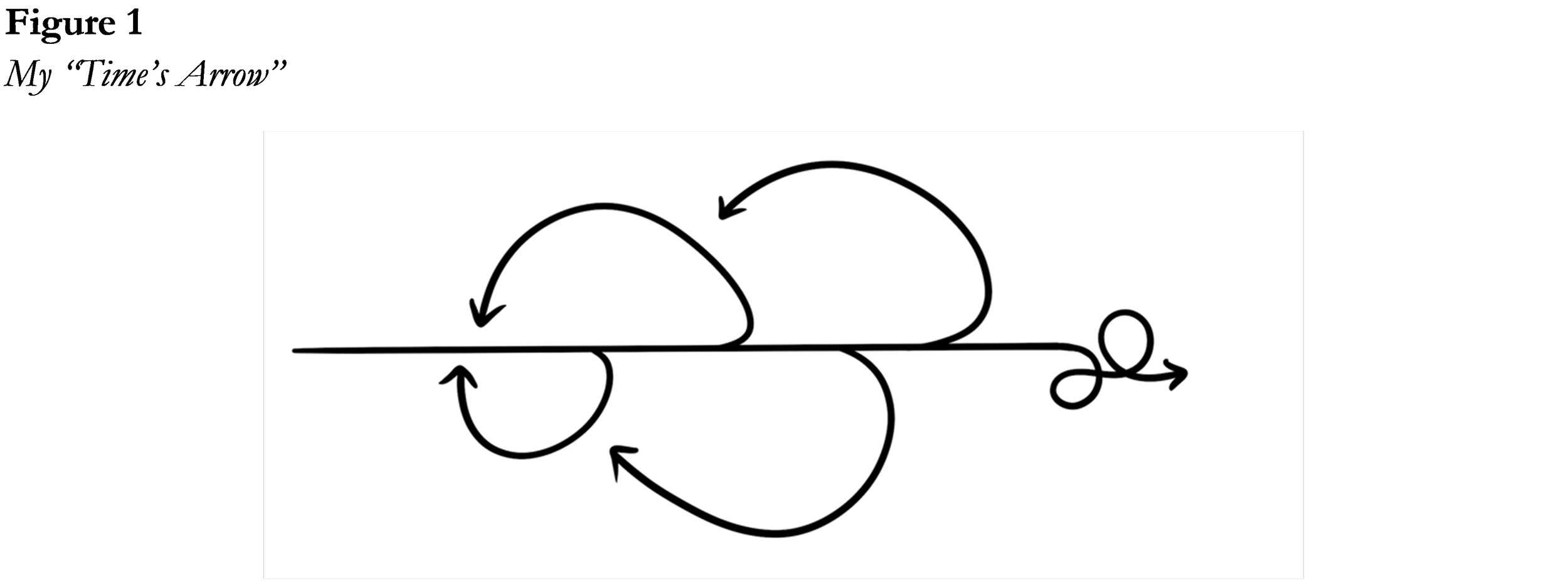

It is a question that plagues me near-constantly, a crisis that ebbs and flows like the tide. For a brief while after writing this entry, I reaffirmed my bisexuality. Two months later, I promptly careened back into confusion. It is a brutal cycle, one that distorts my perception of time, as months pass that feel like days for the lack of progress made, and days pass that feel like months for the terrible drawn-out uncertainty. As a visual illustration of how I perceive time’s passage through the lens of my queer desynchronizations, I sketched the path of my “time’s arrow”: a cyclical ramble where any forward progress invariably loops back to doubt (Figure 1).

Other queer people perceive their temporal journeys to be similarly convoluted: when asked to describe her own “time’s arrow,” Allyna said, “I think it would almost look like… scribbles on a piece of paper. And it’s kind of hard to tell where it starts and begins” (personal communication, November 6, 2021). (I asked her to draw this arrow; she produced Figure 2, a path that loops and twists as much as her signature at the bottom of the page.)

It is clear, then, that queer people harbor a deep awareness of how their temporality diverges from linear chrononormativity—it is an almost unavoidable awareness, as society so relentlessly pushes its cisheteronormative agenda. We are constantly faced with reminders of how our timelines are tangled and delayed compared to the normative ones that surround us.

Thus, the twisting of queer temporalities is not only caused by internal changes, but by external, society-driven factors as well. One common conflict that causes queer people to feel unmoored from traditional temporalities is between them and their cishet family members. Being surrounded by models of chrononormativity—particularly in the case of the mother and father, who must have adhered to cisheteronormative benchmarks to give birth to the queer child—can make the feeling of being desynchronized that much more acute. Learning that my mother began dating my father at the same age I am now was a sobering reminder of my own twisted timeline, reinforcing my temporal estrangement; learning that my grandmother married my grandfather just months older than I am had the same unsettling effect. When one’s family is hostile to one’s queer identity, the resultant desynchronization can be even more profoundly isolating. Sawyer’s family, for example, responded to her coming out with a “hate the sin, love the sinner” outlook; when she brings her girlfriend around, her family members “just view it as ‘Oh, [Sawyer’s] friend is over’” (personal communication, November 5, 2021). To have one’s significant other be obstinately referred to as a “friend” creates a fundamental divide that cannot be bridged by the queer person alone. Instead, she is forcibly detached from her family’s temporality, placed in a perpetual stasis where she will never meet the chrononormative benchmarks her family expects her to because she already is meeting them, albeit in a queer way. The resultant desynchronization is therefore caused not by the queer person themself, but by intolerant outsiders.

Closely linked to familial conflict is the conflict between one’s queerness and religious beliefs; this, too, manifests in a temporal discrepancy that can lead to desynchronization. Religious timelines are often even more rigid than non-religious ones, leading to an even more violent desynchronization for the queer individuals who have been raised expecting to adhere to those timelines and now find themselves unable to. Allyna, whose mother’s side of the family is largely Mormon, describes a typical Mormon timeline: “In the Mormon church, you are sixteen and you are dating boys, and by the time you are eighteen, you are married and going on a mission, and having three kids by twenty-three… it goes very fast” (personal communication, November 6, 2021). In contrast, Allyna has “barely dated anybody”; she feels this difference as though she is “lagging” behind where she should be (personal communication, November 6, 2021). Even for cishet people, though, eighteen is an uncommonly early age for marriage—it is the expectations within the specific religious culture that exacerbate Allyna’s feelings of being desynchronized. Religious conflict can also cause queer people to be caught in a desynchronizing cycle of doubt and questioning, as they attempt to reconcile their perhaps-queerphobic religious upbringing with their newly realized identity. Sawyer, whose southern Baptist upbringing conflicted with her nascent understanding of her sexuality, illustrates this desynchronization as a sort of “squiggly line,” a zigzag showing her identity and temporal position in flux (personal communication, November 5, 2021).

Queer temporality is thus shaped by desynchronizations—but what does that mean for the desynchronized queer person’s life? How does a discrepancy in temporality come to affect their experiences and their relationships—with themself, with other queer people, with society? While no single explanation can encapsulate the vast array of queer experiences, many authors and artists have offered insights and answers; among these offerings is the critically acclaimed 2016 film Moonlight, directed by Barry Jenkins.

The real, heavy impact of queer desynchronization, both internally and externally caused, is brilliantly depicted in one of the final scenes of Moonlight. In this scene, the protagonist Chiron has just reunited with his old school friend and romantic interest, Kevin. We learn that the paths their lives have taken are radically different: while Kevin had a relationship with a woman, even a child with her, Chiron confesses to him that “You’re the only man that’s ever touched me” (Jenkins, 2016). The implication of this quiet, faltering confession is, of course, that Kevin is the only person who has ever touched him. Their encounter happened when they were both in high school; Chiron is now a grown man, a (deliberately) stereotypically masculine one at that. There is a societal expectation that he have more sexual experience than a teenaged fumble on a beach, but his queerness (among other factors—the film is also an examination of Blackness and societal expectations for Black men) has completely altered his ability to meet that expectation. How stark the divide is between Chiron’s and Kevin’s experiences is made brutally clear in this shot (Figure 4).

Here, Chiron hovers near the door of the home of Kevin and his child: uncertain of his welcome and his place in Kevin’s chrononormative world. Kevin’s child’s drawings are pinned to the wall between the two men—thus, the chrononormative development Kevin has gone through that Chiron has not literally stands between them, an impossibly wide gulf of time represented through a kitchen-length of space. Chiron’s desynchronization does not create an untraversable divide—the film ends with Chiron and Kevin sharing a tender moment in bed together—but in this moment, it certainly seems to. Thus, desynchronization becomes a very physical and present driving force in queer journeys.

However, the twisting of queer temporality can also present an opportunity: as Sawyer notes, “as soon as you take yourself out of that synchronization with everybody else, it allows you to find yourself” (personal communication, November 5, 2021). She points out that the cisheteronormative timeline encourages conformity—it is through detaching from that conformity that the self can be found. Chrononormative benchmarks offer an easy, thoughtless path forward; those unable to meet those benchmarks, though, are forced to consider what they want rather than what society wants for them. In this way, Sawyer muses, “[Desynchronization has] allowed me to go on this road of self-discovery that I don’t think I’d have been able to go through if I was on the general timeline of everybody else.” While queer temporal journeys are not as neat and easily traversed as cisheteronormative ones, for all their twisting, cycling, lagging nature—and indeed, perhaps because of that nature—they provide a space for honest reflection and self-discovery. With this self-discovery comes a certain thoughtfulness of intention, as queer people move forward with a better understanding of who they are, what they want, and how they exist in relation to society.

The Undrawn Path

I want a queer found family… I harbor some desperate, lonely, queer hope that I will find my own place in the world, where I fit alongside other people. That’s what you’re supposed to do.

It just… feels wrong, the way I want it.

(E. Meckley, personal communication, October 26, 2021)

Equally as fraught as the queer past and queer present is the queer future. A cisheteronormative future is a known quantity: opposite-sex spouse, children, steady job, suburban home. The queer future is an unknown, making it as terrifying as it is liberating. Questions about one’s identity broaden in scope to become questions about one’s trajectory in life. Small desynchronizations—for example, not having kissed anyone as a twenty-year-old—threaten to balloon into large ones, as the lack of romantic and sexual experience compounds and derails the smooth cisheteronormative path to marriage and reproduction. Fuchs (2001) notes that “[t]he age of major transitions and role changes such as… marrying… is more or less standardized” (p. 181). However, those fixed ages do not factor in the time needed for queer self-discovery, so by the time newly-realized queer people have reoriented themselves enough to look toward their future, it has already started to pass them by. Cisheteronormativity waits for no one—in fact, thanks to “the phenomenon of acceleration, i.e. the earlier onset of sexual maturation in western societies,” cisheteronormativity actively works against queer people attempting to get their temporal bearings long enough to puzzle out the question of their future (Fuchs, 2001, p. 181).

What, then, lies ahead for those experiencing a deceleration, a delay in meeting certain benchmarks? Society offers us no clear answer to this question, presumptive of everyone’s ability and willingness to conform to chrononormativity, and so a liminal ambiguity comes to define the queer person’s future. In her 2016 novel Homegoing, Yaa Gyasi highlights this queer uncertainty through the character Quey, an 18th-century queer member of the Fante tribe, living in modern-day Ghana. Quey, returning from a sojourn to London, is presented with the opportunity to live in the village of his childhood friend and love interest, Cudjo. When Cudjo flirtatiously extends this invitation, Quey’s mind spins with nervous, excited questions:

Why had Fiifi told Cudjo that Quey wasn’t married? Had Cudjo asked? How could Quey be welcomed in Cudjo’s village? Would he live in the chief’s compound? In his own hut, like a third wife? Or would he be in a hut on the edge of the village, alone? … There was a way. There was no way. There was a way. (Gyasi, 2016, p. 65)

Like a straight teenager in a romantic comedy plucking petals off a flower and repeating, “He loves me, he loves me not,” Quey vacillates between hope and fear, possibility and impossibility. However, where “He loves me, he loves me not” is a juvenile game, real stakes underlie Quey’s fluttering uncertainty: will he be able to pursue the non-normative future he desires, one where he fills the same role a wife would for the man he cares for, or will chrononormativity prevail and force him away? Gyasi cements the painful reality of cisheteronormativity’s dominance by answering the question definitively: “Quey would never go to Cudjo’s village,” instead staying in his own and marrying a woman for political purposes (p. 69). Thus, Quey’s ambiguous queer future is stolen from him and replaced with a rigid, clearly delineated cisheteronormative one.

The divide between cishet and queer perceptions of the future was recently made almost comically clear to me. Excited about the success of her own relationship, my roommate offered to guide me along my “love journey.” She sees my future with more clarity than I do: a perhaps winding, perhaps eventful journey through the mysterious—but well-charted—land of heterosexual, heteroromantic love. She sees my future first date, my future first boyfriend, maybe even my future husband.

I couldn’t help but smile at the irony. Her vision of my future is so clear and vibrant—and utterly divorced from my reality. Rather, her surety is nearly antithetical to queer experiences such as Quey’s and my own. My view of my future is hazy, dark; questioning my sexual and romantic orientations means I’ve cast a lot of doubt on what an ideal future looks like for me. I’m not sure if I want to marry, have children, or even date. My roommate sees my “love journey” as though drawn on a roadmap: clear, definite, sensical, unchanging. I see my “love journey” as though through a kaleidoscope in a room lit sporadically by strobe lights.

It is not only the course of one’s past and present that is altered by queerness: so, too, is the future irrevocably rerouted. What my roommate envisioned for me—essentially, what society envisions for me, as my roommate functions as an aggressively straight microcosm of the cisheteronormative public—follows the normative, linear path forward. But since my gay awakening, and many subsequent periods of questioning, I’ve divorced myself from that path so thoroughly I doubt I could find it again if I wanted to.

And crucially: I do not want to. There is a beauty and a uniqueness to the queer future, one that many queer people take great comfort in. One survey of middle-aged queer people participating in Brisbane, Australia’s nightlife shows a purposeful disregard for chrononormative benchmarks—instead, they “continue to participate in conventionally perceived ‘irresponsible and thus less respectable’ scene-related activities,” including attending dance parties and using recreational drugs (Jaffe, 2018, para. 8). This is a conscious rejection of what cisheteronormative society would term “appropriate” adult behavior, a deliberate desynchronization from the chrononormativity that would have them married with kids rather than pursuing modes of life we associate with younger generations. Here, queer separation from normative time is a gleeful choice, reflective of a sense of future not overshadowed by looming cisheteronormative expectations.

Even those queer individuals interested in meeting chrononormative benchmarks—albeit in a queer way—perceive a difference between a cishet person meeting those benchmarks and they themselves doing so. The queer women I interviewed agreed that they want wives and children, but they also agreed that their hypothetical family “means something different” than family does to heteronormative society: “It’s looser, so much less strict than what they tell you is a family” (Allyna, personal communication, November 6, 2021). Family is, then, more “open to what matters to you… than what matters to everybody around you” (Allyna, personal communication, November 6, 2021). And as the queer family is looser, so is the queer future. Removed from the constraints of the spouse-and-two-kids, white-picket-fence, cookie-cutter suburban life, the queer future becomes richer, more diverse. As queer time itself has developed “in opposition to the institutions of family, heterosexuality, and reproduction,” instead embracing “strange temporalities, imaginative life schedules, and eccentric economic practices,” it is only appropriate that a queer future has the potential to be equally strange, imaginative, and eccentric (Halberstam, 2005, p. 1). The desynchronization that permanently altered the queer path now offers a chance for real, radical fulfillment.

Whether this fulfillment is achieved through marrying and raising children, building a found family with other queer individuals, or rejecting the necessity of traditional familial bonds altogether, it is fundamentally set apart from chrononormativity. The rejection of chrononormativity is in fact a critical part of this fulfillment: by allowing themself to give up on cisheteronormative expectations, the queer individual becomes beholden to only themself rather than to society, freeing them to pursue their own version of contentment. As the philosopher Michel Foucault postulated in a 1981 interview: “To be ‘gay,’ I think, is not to identify with the psychological traits and the visible masks of the homosexual but to try to define and develop a way of life” (p. 138). This, then, becomes the goal of the queer future: to construct one’s own way of life outside of normative time, reclaiming and embracing desynchronization in the process. Queer communities and families thus form “bubbles” in the normative time stream—ones they have no desire to rupture.

Conclusion

Looser, non-linear, sometimes even lagging, but not lesser: instead, the queer temporal experience is rich, varied, and unique. It is characterized by repeated and significant desynchronizations, all of which contribute to altering the queer individual’s previously straight temporal path. From the moment the queer person recognizes themself to be queer—and, in some cases, even before that—they are subject to an uncoupling from cisheteronormative time that will influence every aspect of their temporal experience. Such a radical departure from normative time offers as many opportunities as it does uncertainties, with only one guarantee: a straight timeline is no longer possible.

The radical impacts of desynchronization that make it so initially disturbing are also what make it such a promising route of empowerment. Beginning with the second “birth” of the queer individual, desynchronization opens avenues for introspection and self-discovery, avenues that eventually lead to a self-defined mode of life where personal fulfillment is within reach and the realities of queerness are embraced. Desynchronization can be frightening, yes. It can be isolating, true. It is also strange, imaginative, and eccentric—in a word, revolutionary. Thanks to the freedom it offers from chrononormativity’s constricting influence, whatever doubt might saturate the queer past, there is great hope to be found looking forward to the queer future.

At the end of our interview, smiling down at the paper where she sketched her time’s arrow curving optimistically upward, Sawyer confided: “I would say I’m on the up-and-up.” I like to think that, no matter the twists along the way, all our arrows will end up pointing in that very same direction.

Evelyn Meckley is a freshman at the University of Florida, where she is currently pursuing a degree in English. Evelyn has long harbored a passion for storytelling in all its forms—with a particular focus on queer themes and theories—and hopes to one day be a published novelist in her own right.

References

Foucault, M. (1997). Ethics: Subjectivity and truth (P. Rabinow, Ed.). The New Press. (Original work published 1954–84)

Fuchs, T. (2001). Melancholia as a desynchronization: Towards a psychopathology of interpersonal time. Psychopathology, 34(4), 179–186. https://doi.org/10.1159/000049304

Gyasi, Y. (2016). Homegoing. Penguin Random House.

Halberstam, J. (2005). In a queer time and place: Transgender bodies, subcultural lives. New York University Press.

Jaffe, S. (2018). Queer time: The alternative to “adulting.” JSTOR Daily. https://daily.jstor.org/queer-time-the-alternative-to-adulting/

Jenkins, B. (Director). (2016). Moonlight [Film]. A24; Plan B Entertainment; Pastel Productions.

Stockton, K. B. (2009). The queer child, or growing sideways in the twentieth century. Duke University Press.